Clarity and security through standardised delivery conditions

Incoterms, or The International Commercial Terms, created by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), are intended to ensure that delivery terms are clear and unambiguous, so that they can be used when drafting contracts. The first version of the Incoterms was drawn up in 1936 and has been revised repeatedly in line with new developments in the transport sector. The current Incoterms are the Incoterms 2020: Here, some sensible adjustments and changes have been made to react to current trade practices and simplify the choice of the appropriate Incoterms. Explicit reference is made to the usability in national trade.

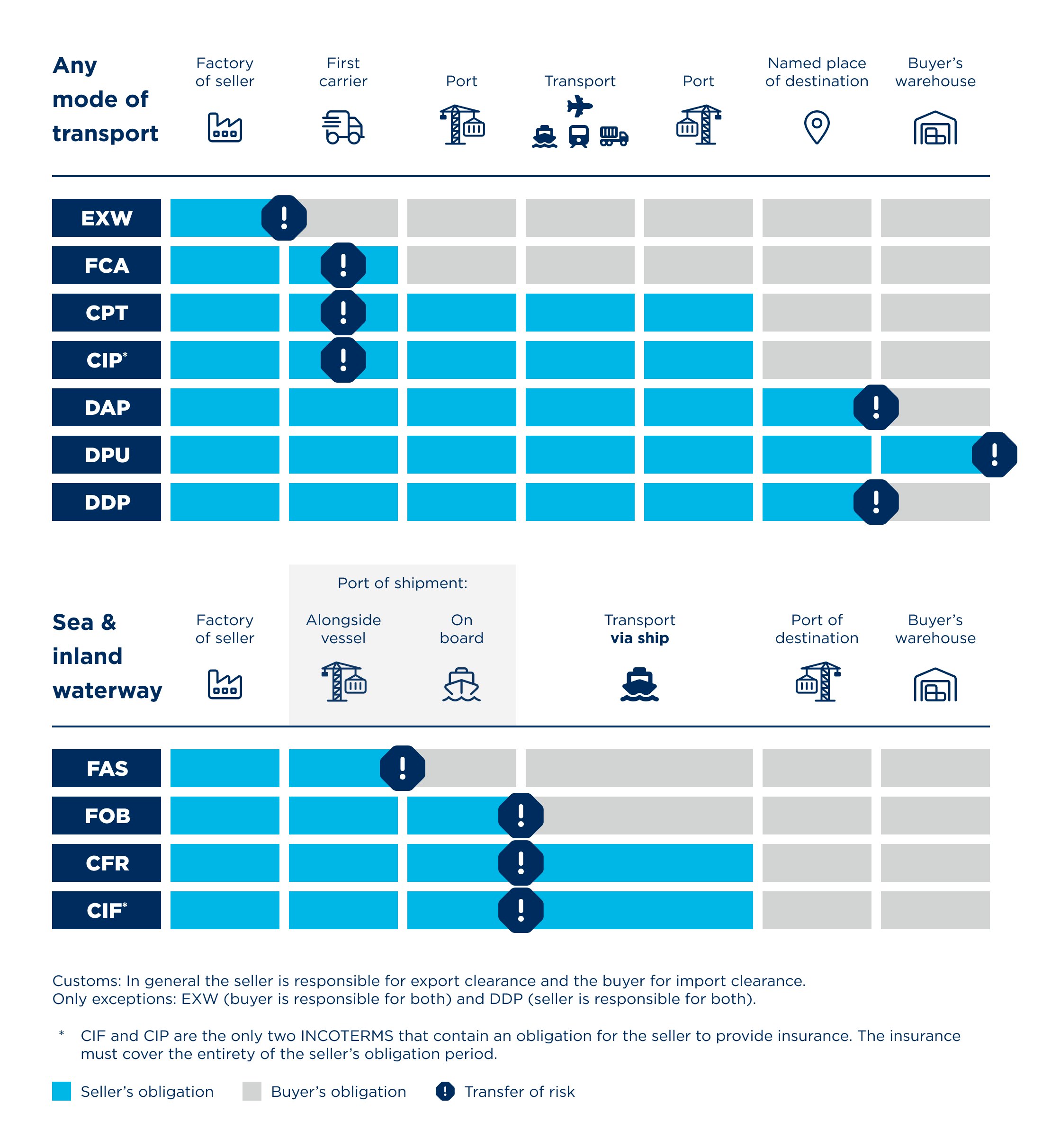

Below you can view the Incoterms 2020 chart, jump directly to the current Incoterms 2020, or get information on Incoterms 2010. Older Incoterms are still valid and can still be used if both contracting parties expressly agree on them. Otherwise, you can find more detailed information on the subject of Incoterms below.

Incoterms in general

Incoterms regulate the transport of movable goods whose purchase has been concluded. The delivery clauses standardised in the Incoterms can be part of a purchase contract, but do not replace it. The focus is on the question: Which of the contracting parties assumes (from when) costs and duties, risks as well as obligations from transport to insurance to the provision of freight documents? The origin of Incoterms lies in overseas trade, which can be seen in the typical terms from "freight" to "free on board (FOB)". In the meantime, Incoterms "multimodally" regulate all forms of transport from overseas and inland shipping to air freight and transport by road and rail. In addition, there are Incoterms whose application is intended for sea and inland waterway transport (FAS, FOB, CFR and CIF).

Incoterms are recognised worldwide and are available in more than 30 languages. In the event of any dispute regarding interpretation, the English version shall prevail.

Incoterms 2020 Overview

Other aspects of Incoterms in logistics

In addition to the main functions mentioned above (regulating transport costs and obligations as well as the transfer of risk), Incoterms also deal with other elements. The question is always which side of the contract takes care of what and/or who bears the costs.

- Goods documents (licences, certificates of origin, certificates etc.)

- Transport documents (delivery note, bill of lading, waybills ...)

- Insurance (what is insured and to what extent, from minimum coverage to "all risks")

- Information requirements

- Goods inspection

- Packaging (suitable material, inspection obligations, labelling (e.g. as dangerous goods))

Important: Incoterms are only valid if jointly agreed

Incoterms are not a law but an offer by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) to use certain standards or established commercial practices. They must be contractually agreed including the year (e.g. Incoterms 2020). If no year is specified, the current version will be used. Furthermore, precise location information is important (port of shipment, port of destination, delivery or merely "named place"). If the exact place is missing, the seller can choose the best place from their point of view.

No status as General Terms and Conditions (GTC)

If you want to effectively include Incoterms in a contract, an explicit reference must be made. A good place to do this is by mentioning the Incoterms in connection with the purchase price and payment terms. If Incoterms are merely specified as part of the GTC, there is a risk of being considered a "surprising clause" in court and thus ineffective. Furthermore, it may happen that the buyer and seller each have Incoterms in their GTC that contradict each other, which leads to a "battle of forms" in which contradictions neutralise each other.

To avoid these risks, Incoterms should be clearly listed and used by the contracting parties by mutual agreement.

Variation of Incoterms: possible, but usually not advisable

As standards or blueprints for terms and conditions of delivery, Incoterms are a tool for drafting contracts efficiently and unambiguously. As they are not laws, they can also be individually modified. However, this is rarely advisable, because it means they lose their value as globally recognised, unambiguous standards. Instead, it opens the door again to misunderstandings, which Incoterms are supposed to remedy.

Possible example for Incoterms modification: With the delivery clause EXW (Ex Works), the seller only has to provide the packed goods, the loading would in principle already have to be carried out by the forwarding agent commissioned by the buyer. Now it can be agreed that the seller takes care of the loading - but the buyer still bears the risk. Alternatively, the FCA clause can be used, in which the loading and the risk are borne by the seller.

Limits of the Incoterms

Incoterms have a great benefit. They regulate a lot, but not everything. That is why it is important to know their limits.

Areas not covered by Incoterms:

- When is a purchase contract concluded?

- Retention of title and transfer

- Terms of payment

- Applicable law or legal consequences in case of breach of contract

Furthermore, if Incoterms come into conflict with e.g. foreign trade or customs law, the latter are always considered public law, whereas Incoterms as part of private law are subordinate to them.

UN Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods and BGB as basis and supplement to the Incoterms

The UN Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG) is applied to international goods transactions. In many cases it is complementary to the Incoterms, i.e. both are often coordinated with each other. Terms such as goods, place of performance, delivery and place of delivery are not defined in more detail within the Incoterms; the UN Sales Convention is referred to as a basis in the introduction of the Incoterms.

In national transactions, the laws of the BGB also apply. Typically, the CISG is used before the BGB, as it takes precedence as a special law (lex specialis) over general laws. In turn, Incoterms can override ("waive") individual fundamental provisions of the CISG, otherwise the rest of the CISG remains valid. However - as already mentioned - the CISG assumes sales contracts of contracting parties with branches in different countries, the Incoterms only require the transport of goods (i.e. also in the domestic country or domestic markets such as the EU).

Determination of the transfer of risk

The regulation of the transfer of risk is an important point, as damage or loss etc. of goods during transport occurs time and again. Legal regulations on the transfer of risk are "dispositive", i.e. they can be agreed individually between parties. If the basic regulation on the transfer of risk from the CISG (Articles 67 to 69) is not desired, individual delivery conditions or standardised delivery clauses such as the Incoterms can be agreed. Jointly, the transfer of risk is brought forward or back by the buyer and the seller. Otherwise, in the CISG and also in the BGB, the rule is that the risk passes either when the goods are delivered to the agreed destination or - if no place has been determined - when they are handed over to the first carrier. The goods must be clearly attributable to the contract by means of marking, transport documents or other means.

Additional: The moment of the transfer of risk is at the same time the booking day as the transacted turnover. If you want to bring forward the transfer of ownership for balance sheet reasons (e.g. in the case of longer sea transports where you do not want to wait for the arrival including the transfer of risk), order documents such as the "bill of lading" can bring about the transfer of ownership in advance. The handover of the bill of lading to the buyer counts as the handover of the goods themselves.